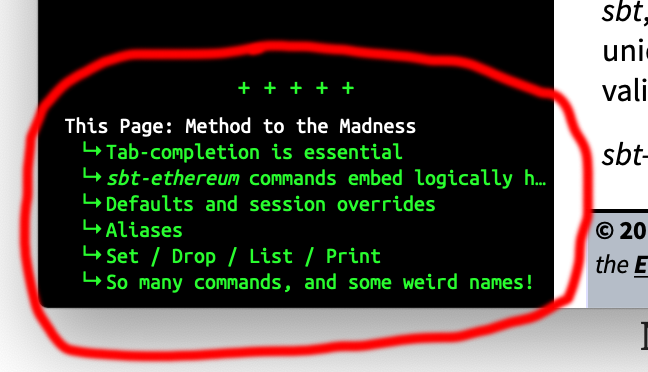

Method to the Madness

sbt-ethereum intends to make interacting with, customizing, and deploying Ethereum smart contracts more “accessible” to non-developers. But, at first glance, it might seem bizzarely complicated. First, of course, it’s old-school. It’s a terminal-based application rather than a GUI-style app. But even beyond that, it has zillions and zillions of really long, weirdly named, impossible-to-type commands. How is this supposed to be “accessible”?

But there is some method to this madness. Once you master a few tricks and regularities, the apparent complexity becomes easy to manage.

While working with these docs, use the page tables of contents!

In the bottom of the left column of these docs, for every page, there is a page table of contents.

You’ll find navigating this documentation much easier if you get into the habit of glancing at that!

Tab completion is essential

sbt-ethereum command names are really, really, really long!

On the bright side, the names are pretty descriptive! You don’t need to memorize what terse incantations like jzn or kxl do. Commands in sbt-ethereum look more like ethContractAbiDefaultSet, which does give some clue. Kind of. (See below!)

But you really, really, don’t want to type out long names like that.

sbt, the platform on which sbt-ethereum is built, offers tab completion. You can type the first bit of a command and then hit the <tab> key. If there is a unique completion, or even partial completion of the command, sbt will fill it in for you. If not, it will present for you a list of commands that might validly complete what you’ve started, so you can add a bit more.

sbt-ethereum relies upon tab completion aggressively. Not just command names, but also command arguments, can often be tab completed.

You want hitting <tab> a lot to become muscle memory.

sbt-ethereum commands embed logically hierarchical menus

With just a few exceptions, sbt-ethereum commands begin with eth. Beneath eth are the following “submenus”:

AddressContractDebugKeystoreNodeShoeboxTransaction

Logically, the ethAddress* commands help you manage and monitor Ethereum address, ethContract* let you interact with smart-contract-specific information, etc.

Note that none of these “submenus” share the same first letter. That is by design. You never have to type more than one capital letter before hitting <tab> as you “navigate” this command hierarchy. If you want to look up the balance of an address (in Ethereum’s native cryptocurrency “Ether”), you just type

ethA<tab>B<tab>

which expands to

ethAddressBalance

The same is true for very long commands. To type ethContractAbiDefaultSet, it’s just ethC<tab>A<tab>D<tab>S, or ethCADS with some twitches towards tab interleaved.

Defaults and session overrides

To interact with Ethereum smart contracts, a lot of stuff has to get set up. There needs to be a “Chain ID” and “Node URL” defined. Usually, you’ll also want to have a sender address configured, and an “ABI” associated with the smart contract you mean to talk to. (An ABI is basically a description of how applications, including sbt-ethereum, can communicate with a smart contract.)

For all of these configurable elements, sbt-etherum lets you define defaults, which get permanently stored in sbt-ethereum’s internal database. Often, you can just use these defaults, so you don’t have to mess with configuration very much.

But sometimes you need to do something different. Maybe you need to send a transaction from a different address (think identity or account) than usual. Maybe you are working with a different network than usual.

All of the items for which defaults can be configured permit session overrides. If you define a session override, the new value you provide becomes active, but only for the rest of your “session”, not permanently. When you quit and restart sbt-etherem, the values will have reverted back to their defaults.

Examples of items with defaults and overrides include:

ethAddressSender*ethContractAbi*ethNodeChainId*ethNodeUrl*

Some items do not usually need to be configured, because sbt-ethereum can compute reasonable values automatically. However, they have overrides for when you want more control than the default behavior would offer. These include;

ethTransactionGasLimitethTransactionGasPriceethTransactionNonce

Aliases

Working with Ethereum, you frequently need to refer to Ethereum “addresses”. By default, these are long strings of gobbledygook hex like 0x82ea8ab1e836272322f376a5f71d5a34a71688f1.

Never try to type an Ethereum address! It’s way to easy to screw up, and if you send value to a bad address, it’s lost forever. You can copy, paste, and then carefully verify addresses, but that gets tiresome. So sbt-ethereum encourages you to define more natural address aliases that you can type (almost) wherever sbt-ethereum expects an address.

Similarly, in more advanced scenarios, it is sometimes useful to be able to refer to contract “ABIs”, which are descriptions of how an application can communicate with a smart contract. sbt-ethereum permits aliases of these as well. ABI aliases begin with abi:. There are also some standard ABIs defined, such as abi:standard:erc20.

You’ll find alias related commands under

ethAddressAlias*ethContractAbiAlias*

Set / Drop / List / Print

For both configurable items (both defaults and overrides) and for aliases, sbt-ethereum adopts a consistent set of conventions for accessing and manipulating values.

*Setcommands define the values of configurable items or aliases*Dropcommands remove values you have previously set*Printcommands prints to the screen, not a printer a single currently effective value*Listcommands prints a list of defined values where there might be many

So many commands, and some weird names!

If you start with seven configurable items, each of which can take default and override forms, and multiply that by the four conventional subcommands (Set, Drop, Print, List), you get 56 commands. Add the conventional subcommands for the aliases and you get 8 more, to 64. That’s an overestimate — not all the seven configurable items accept defaults, not all are listable — but hopefully you can begin to understand why there are so. many. commands.

But they all do basically the same things in basically the same ways, so if you understand that, hopefully they are less intimidating.

Commands sometimes have weird names in order to ensure that you never have to type more than the first, capital, letter of a segment. For example, there is a command called ethAddressAliasCheck that basically looks up the address associated with an alias. It might have been more natural to call this command ethAddressAliasLookup, but that would have collided with ethAddressAliasList — typing ethAddressAliasL<tab> would have remained ambiguous. Check was chosen in place of Lookup after ethAddressAlias to prevent this ambiguity.